Fields Fallowed and Fauna Returned

A few weeks ago I traveled from Austin to meet my father and knock out a few winterization chores on our family’s land in southwestern Oklahoma, near the community of Headrick in Tillman County. As I returned from the trip, I realized I had never written much of substance about the place and thought it worthwhile to share a few thoughts and experiences. It is a rich confluence of stories in history, heritage, power struggle, and sustenance, as land often is to the people who find themselves living on it. The words that follow were largely dictated into my notes app while I was driving and may sprawl a bit, but are no less true.

The land, which currently spans some 311 acres, was originally patented by the United States Bureau of Land Management to my great great grandfather, Orren Benjamin Walker, on February 4, 1909 as a 160 acre grant. I have been learning a great deal lately of the political climate and all that white settlement brought to what is now called Oklahoma, where my family’s land is. From the turn of that century, much of the reservation land originally deeded to various tribes in the Lawton, OK area was “opened” for the taking by white settlers. My family fits the pattern of westward moving Irish and British descendants in the US (not too distantly immigrants to this vast land themselves) into what was long considered Comancheria. I have also been learning as much as possible about the Comanche people lately. The story of nearly every inch of land I encountered growing up, both residing and traveling, is descended from the not-too-distant lands ruled by the Comanche empire, yet so little of their impact was explored in the propaganda the Texas public school system called “Texas History.”

But I digress.

The Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867 established a reservation in the southwestern part of Indian Territory for the Kiowa, Apache and Comanche tribes (one can still see the signage at the boundaries of this original reservation despite its diminished borders) where my family’s acreage sits today. But with the passage of the indefensibly racist Dawes Act (coincidentally signed into law on my birthday had I been born in 1887) aimed at assimilating Native Americans into “white society,” there were commissions formed across Native reservation land to negotiate with various tribes and encourage assimilation measures. The foremost assimilation measure in the mind of these commissioners was to enforce the process of allotment - the parceling of tribal lands into individual plots instead of indigenous people’s traditional means of living communally/nomadically/freely in bands and villages. The Dawes Act explicitly sought to destroy the social cohesion of Native American tribes and to thereby eliminate any remaining vestiges of Native culture and society. What better way to disappear a culture than to take its last remaining lands and force their relationship to land to one of white invention? In Southwestern Oklahoma, The Jerome (or Cherokee) Commission set out to force local tribes to accept reservation allotment and to sell the subsequently “surplus land” back to the US government so that it could be settled by whites. Except for the Cherokee, they focused on the tribes in western portion of what was known as “Indian Territory” and is now known as Oklahoma. These tribes included the Iowa, Sac and Fox, Potawatomi, Shawnee, Cheyenne and Arapaho, Wichita, Kickapoo, Tonkawa, Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache.

Advertisement for the sale of Native American land. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

The results of this process was the surrendering of much of the land in Southwestern Oklahoma, which was then patented to white settlers who wished to scratch out a living via farming and ranching across that rugged terrain. The first lottery was held on August 6, 1901. It was followed in 1906 by the "Big Pasture" Lottery, in which my ancestors acquired the acreage that remains in our family’s legal ownership today. Tillman County itself was founded at the time of Oklahoma statehood in 1907, and was named for Senator Benjamin Tillman of South Carolina, who was an unabashed white supremacist and flaunted a strange mix of career achievements. He was instrumental in the founding of Clemson University, was often politically ostracized for his open and unapologetic disparagement of Black Americans and still considered a great orator, was responsible for the first campaign finance act to ever be passed into law (banning corporate contributions), and was instrumental in passing South Carolina's 1895 constitution, which disenfranchised most of the black majority and many poor whites. And to this day this tiny little county in Oklahoma bears his name.

Situated on a bend in the North Fork of the Red River in the Wichita Mountains, the acreage in Tillman County is a rugged place. Many people are unaware that there are mountains in Oklahoma so it’s worth noting that the Wichita range is a scattered range of rocky promontories and rounded hills forged of red and black igneous rock, light-colored sedimentary rock, and boulder conglomerates. In nearby Greer County sits a notable peak called Quartz Mountain (also called Baldy Point) that is worth a climb if you find yourself in the area. With the lichens and moss that grow on their northern surfaces, the sea sage and grasses that surround them, these are mountains that express same color palette as the western diamond back rattlesnake’s camouflage. When I first took Sierra out to the family place, she had a near encounter with a good sized rattler sunning itself on a December day on “Grandad’s Mountain” that earned her the nickname Snake Charmer from my grandfather.

“Grandad’s Mountain”

My grandfather and his melons in the back of the old Chevy S-10 (we’ve still got that truck)

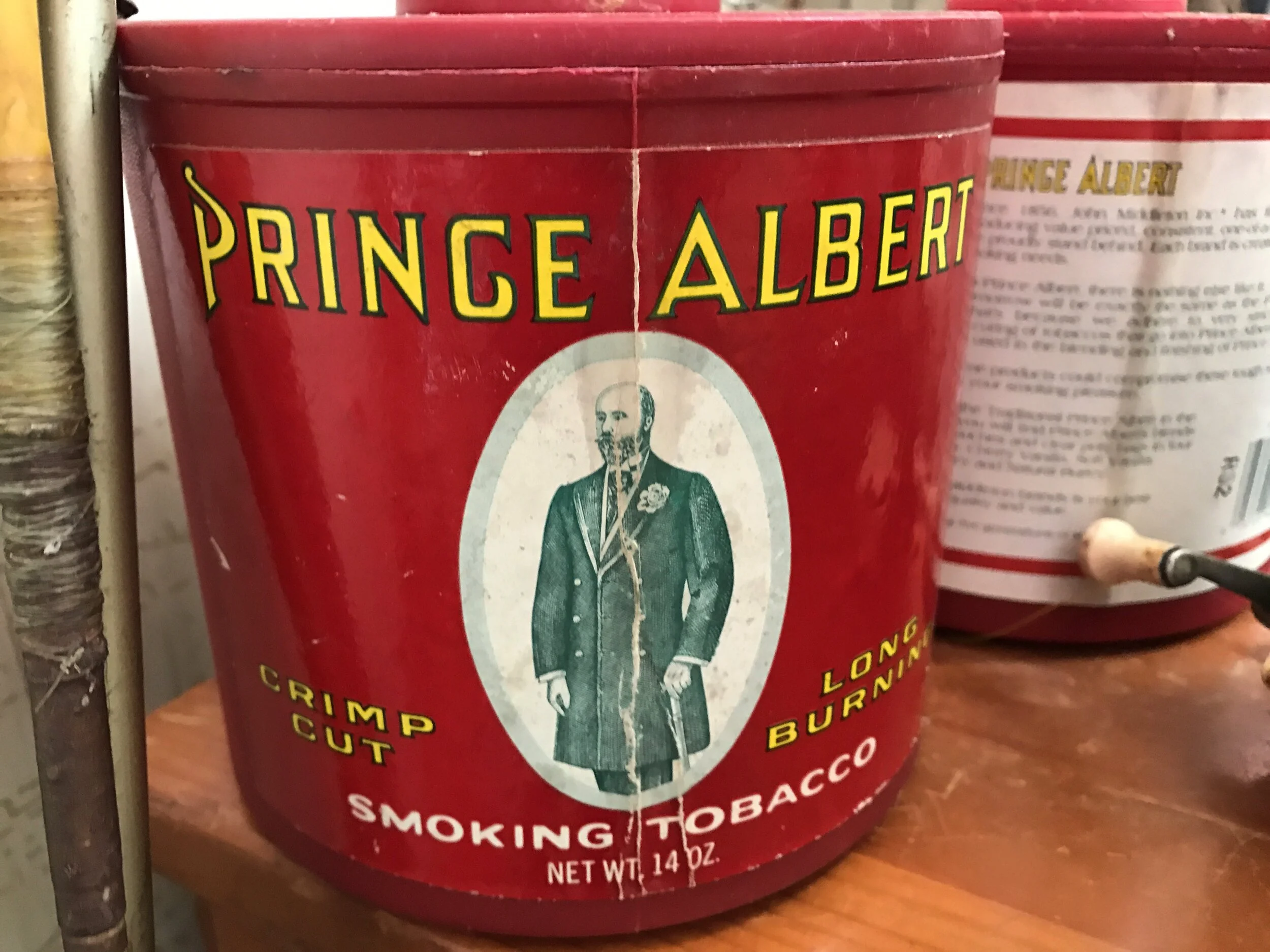

I spent a great many sweltered and swollen summer days on the land with my grandfather. The house was an old Air Force barracks moved to the farm from the nearby base. Our work consisted of watering and tending to the cattle, maintaining equipment, and keeping the land healthy. In the mornings before the heat set in, we’d gather from the fields our cantaloupe, watermelon, black eyed peas, plums, tomatoes, squash, and corn to sell to local markets and from the bed of the truck beneath the abandoned gas station awning in town. I negotiated a twenty percent take of what we made from the groceries and passersby, storing the bills in an old Prince Albert crimp cut long burning smoking tobacco container where I saved up enough paper to buy my first pair of Nikes (black and white suede Cortez). The money smelled like stale vanilla.

After the chores were done, my grandfather would sometimes take soap down to a cattle trough fed by our well and bathe there. I was free to run wild. I’d head up the mountain with my pellet gun, following after the dogs, Ace and Duce, to dodge sunning rattlesnakes and try to find a skunk we could harass. When we could only turn up grasshoppers in lieu of vermin, the dogs and I would run together down the mountain, across the sand pit, through the shelter belt, and down to the sandy salty North fork of the Red River that wound its way through our place where I could swim naked in the red and muddy brine. I once made the mistake of wearing white underwear into that slow river to the consequence of permanent ruddy discoloration, like rusted steel. And although my uncle would eventually develop a tie dye technique with the river water, swimming nude became my preferred alternative.

A Southwestern Oklahoma piggy-bank.

The nights on that land were so dark, you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face when the moon waned. I remember when my great-grandfather passed into death in the front bedroom (where I typically slept when I was there) and the cattle sauntered up to the house as if they knew their friend had left for a party they couldn’t yet attend. That night was particularly dark as the taxidermy bobcat atop the television, now in sad decay, stared back in wild surprise at us in mourning and in misunderstanding.

My earliest memories of the farm span years before even those sweaty summers picking black eyed peas and spending the afternoons in front of the window unit of the house. I remember fractured scenes from the days when my great grandparents were alive and well, farming the land as they had done for much of their lives. There is a blurry memory of my uncle walking my cousin and I up to the top of grandad’s mountain. Another memory of my great grandfather taking his false teeth out and scaring the hell out of me still rattles around in my mind. My great grandmother’s larger than life persona, gravitas, and felt presence in any room stands out. I remember my grandfather’s numerous sisters in constant conversation. I remember the pecan trees out in front of the house. I remember learning what a tick was for the first time and feeling terrified that a blood thirsty thing could move so freely without detection. Though I did not know its particulars as a boy, the land had a special feeling about it and this feeling was reenforced by the reverence my parents, aunts, uncles, and grandparents felt for it.

Being there again in late September gave rise to familiar sensations of nostalgia; the scent of my great grandmother’s 1987 Chevy S10 caked with literal decades of dust and sweat, the taste of fresh well water from the tap near one of the stock tanks, the creaking of the fallen windmill as it turned slow in the early autumn winds, and the prick of grass burs in my fingertips as I picked them from my pant legs. The sting reminded me of winter days passed, marked by bloodied hands at the cause of cotton seeds or barbed wire.

My great grandfather, Lonzo Jefferson Walker

My great grandparents at their 50th anniversary party

The last decade or so, the land has been undergoing profound change. It is no longer farmed in the sense that it was in my ancestors’ tenure. The fields that once yielded crops are buried under 6 foot, nutrient rich grass mixes; fescue, bluestem, wild johnson, Sorghastrum nutans, rye, and even wild radish. The efforts to bring grasses back to the land were brought on by the financial sustenance provided by Conservation Reserve Program, managed by the United States Department of Agriculture’s Farm Service Agency.

The CRP pays us a yearly rental payment in exchange for removing environmentally sensitive land from agricultural production and planting species that will improve environmental quality. In a twist of disarranged irony, the same government that overthrew these lands and forcibly took them from their indigenous inhabitants, allowed white settlers to rampantly overindex the soil’s carrying capacity (causing the famous and tragic dustbowl), now pays the ancestors of those settlers to return the land to some version of the wildness that once was. And the program, while specifically debated by scientists and policy advisors, is not completely without merit. Broadly speaking, the CRP has worked to address a large number of farming and ranching related conservation issues, including drinking water protection, reducing soil erosion, wildlife habitat preservation, and the preservation and restoration of forests and wetlands. So now stand grasses well above my head, swaying in the winds that sweep across the mountain range.

As the fields have fallowed, the clearly marked and fenced patches of soil I remember from childhood have radically transformed to a version of their wild and native self. It looks and feels less delineated and more a whole; a cinematic quality pervaded as though someone reminded the place in a whisper to return to a state of wilderness, indistinguishable from the sprawling country. Humans were no longer in charge. Although there are pieces of ancient farm equipment dilapidating, scattered like bird shot across the land, nature has returned in a strong showing and from the sandy soil is growing a habitat unfamiliar with human beings. I assure you, it’s no struggle for that land to swallow and stuck even the most powerful of pickup trucks.

In the few short days we spent there in late September, we saw wildlife so abundant and active that you might assume we were camping in a wildlife preserve. Listening to the eerie calls of a barred owl in the trees directly above our tents, we could clearly make out the yip and bark of coyotes running wild in search of the rare rabbit. A trudging porcupine shuffled its way across our campsite. There was ample evidence of bobcats, turkeys, white tail deer, raccoons, skunks, and rattlesnakes. We were visited by scorpions and mantis, red tail hawks, and turkey vultures. A covey of quail curved their way through the plum thickets. Sage brush crunched beneath boot, releasing its scent into the wind. There was an electric energy moving through the place, which had the effect of bringing one’s heightened awareness to the center of mind. We were not alone.

Fresh tracks

The days were hot, but sufficiently tempered by constant breeze through the shelter belt of Osage Orange trees where we set up camp. When we ventured into less windy areas, we sweltered. Between chores, my dad and I took the opportunity to take a dip in the North Fork. I’d taken Sierra and Luna out there a few years back in the dead of winter and was surprised by how much the river has moved itself since then. It has taken a nearly completely new path since I was a boy.

The river is geologically and historically significant, if only regionally. From its source in central Gray County, Texas, the river flows eastward, passing through Wheeler County, Texas, into Oklahoma. Just west of the Wheeler county line, it is joined by McClellan Creek, its chief tributary. On the Oklahoma side of the border, the stream flows east across Beckham County where it is joined by Sweetwater Creek and then turns southeast to form the county line between Greer and Kiowa counties, where it is impounded to form Lake Altus-Lugert (Altus is where you go if you need a cafe meal or hardware and sundries from the farm supply store). In southern Greer County, the North Fork joins Elm Creek before turning southerly, forming the border between Kiowa County and Jackson County, Oklahoma, and Jackson County, and Tillman counties (where the family land sits). It joins the Prairie Dog Town Fork of the Red River (which also carved the famous and homesickness inspiring Palo Duro Canyon further into the Texas Panhandle) at the Texas-Oklahoma border.

Of more recent historical interest, and just a few decades before my family settled along the river’s banks, the Adams-Onis Treaty defined the Red River as the boundary between the United States and New Spain in 1819. The North Fork was considered to be a significant part of the boundary. The Marcy Expedition of 1852 reportedly “discovered” that the main channel of the Red River was actually the South Fork of the Red River, now named Prairie Dog Town Fork of the Red River, although this fact was known to indigenous people for centuries. The U. S. government claimed the land between the two Red River streams as far as the 100th Meridian as part of its own territory, despite this land’s true power center, both in commerce and military control, would fall squarely in the Comanche’s grip for decades to come. After the Republic of Texas joined the United States, Texas still claimed the area, which it named Greer County. A lawsuit brought by Texas against the United States was litigated before the U.S. Supreme Court and won by the United States. As a result, Greer County, Texas became a part of Oklahoma Territory and the North Fork ceased to be the Texas boundary. Shifting boundaries and borders litter the history of land we now take for granted as “Texas” and “Oklahoma,” ad nauseam.

The river also served as the site for a battle that would lead to a full fledged war between the two powers of the United States and the Comanche empires. In early 1872, as tensions between the U.S. and the Comanche grew over land disputes, the new Military Commander of the District of Texas decided it was time to strike at the Comanches in the heart of their homeland on the Comancheria, much as the vicious Texas Rangers had done 14 years before at the Battle of Little Robe Creek. This campaign was among the more ambitious ventures into the staked plains of Comancheria by white imperial forces, given the history of the Comanche keeping Spain, Mexico, France, and the U.S. at bay for hundreds of years.

On September 28, a scouting patrol under Lt. Boehm and Captain Wirt Davis, discovered a large Kotsoteka Comanche village. The cavalry reportedly moved within a half mile of the village before they were seen by the villagers, at which point army charged the village, capturing it after a half-hour battle. Mackenzie lost three men and three were wounded. The Comanche lost an estimated fifty or more, including the famed Chief Kai-Wotche and his wife, who were both killed. About 130 Comanches, mostly women and children, were taken prisoner and the army were able to capture some 3000 horses, which were the primary currency and power source of the Comanche people. As justification for the attack, the U.S. army claimed it found overwhelming proof of the band's raids on white settlements in the wreckage of the village.

The blood spilled there in the name of white supremacy over the Comanche and their range lands no doubt washed eastward through the land my family has called their centurial home. I bathed in that saline water and wondered how many countless indigenous people had done the same well before me or my family. My dad noted that his shot of me trudging through looks a lot like a Bigfoot sighting.

I do not know what is in store for this land in the future. As my father and aunts have taken on ownership and stewardship, I imagine things will change trajectory some from the vision my grandparents had for it, just as their vision likely changed from the generation’s previous. Whatever approach is taken, it will be a collaborative effort between my aunts and dad. It’s my hope that restorative and regenerative measures continue to take priority in its management. Otherwise, its foolhardy for me to assert any sense of ownership nor try and project what the world holds in store for our species and those of the land we call a farm.

It is a strange thing to wrestle with the notion that this land and its continual inheritance since 1909 is the exact thing that’s meant when we hear about generational wealth gaps. Of course, I highly doubt many people these days are salivating at the opportunity to go and scratch out a living on a rough piece of land in Southwestern Oklahoma and the land is not making my family rich by any meaningful measure. But I have to ask myself the honest question - at whom’s expense did this land make its way into my family’s possession? Certainly the tribes forced into allotment and who still live nearby today. Is this land not rightfully theirs? Of the 100,000 some odd “Boomers” who made their way to Oklahoma in the first land run, only 42 were Black. Why were there not more, especially given the post secession war promise of 40 acres and a mule?

Can land actually belong to anyone? It outlasts us all and, as is evidenced, its wild state will thrive given the chance.

This old farm is a land of confluence - of specie, of elements, of history, of heritage. It has seen pain, sorrow, joy, and the unbounded flourishing of all things wild and untamed. It’s also seen barbed wire, cloven hooves, drought, incomprehensible dust storms, and tornadoes. Countless indigenous feet have walked its terrain. My lineage has plowed its fields. What it will become is far outside the grasp of my control and, if I’m honest, even my influence. Regardless, I will be here to bear witness and tell its story.

I’ll part with this stanza from Leaves Of Grass—

“O lands, would you be freer than all that has ever been before?

If you would be freer than all that has been before, come listen

to me.

Fear grace, elegance, civilization, delicatesse,

Fear the mellow sweet, the sucking of honey-juice,

Beware the advancing mortal ripening of Nature,

Beware what precedes the decay of the ruggedness of states and men.”